Introduction

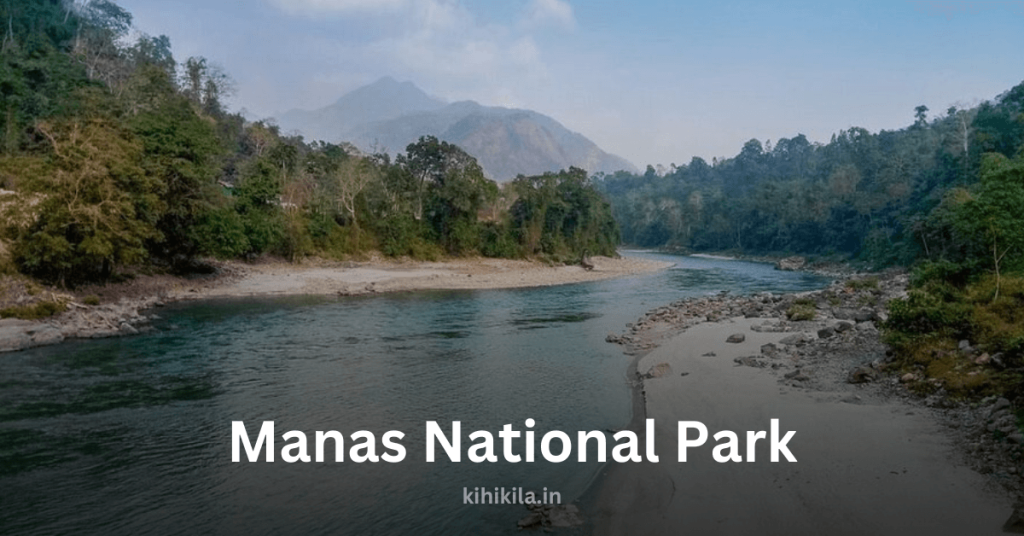

Manas National Park, nestled at the foothills of the Himalayas, is one of India’s most extraordinary wildlife sanctuaries. Known for its breathtaking landscapes and rich biodiversity, this park is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a Project Tiger Reserve, an Elephant Reserve, and a Biosphere Reserve. Spanning across multiple districts of Assam, this unique ecosystem is home to some of the world’s rarest and most endangered species.

A Historical Perspective

Manas was designated as a wildlife sanctuary in 1928, covering an initial area of 360 sq. km. Over the years, it was expanded, attaining the status of a Tiger Reserve in 1973 and a National Park in 1990. Before its official recognition, it was a reserved forest used by the royal families of Cooch Behar and Gauripur as a hunting ground. In 1985, UNESCO declared it a World Heritage Site, and in 1992, it was listed as a World Heritage Site in Danger due to poaching and insurgency. Conservation efforts over the years have played a vital role in restoring its lost glory.

Unique Ecosystem and Diverse Biomes

Manas National Park boasts two distinct biomes, making it one of India’s richest wildlife habitats.

The Grassland Biome

This biome supports endangered species such as the Pygmy Hog, Bengal Florican, Indian Rhinoceros (which was reintroduced in 2007 after local extinction due to poaching), and the Wild Asian Buffalo. The tall grasslands provide an ideal refuge for many herbivores and ground-nesting birds.

The Forest Biome

This dense forest ecosystem is home to species like the Slow Loris, Capped Langur, Wild Pig, Sambar Deer, Malayan Giant Squirrel, and the Great Hornbill. The thick canopy offers shelter to numerous primates and rare avian species, making it a paradise for wildlife enthusiasts.

Rare and Endangered Wildlife

One of the most remarkable aspects of Manas National Park is its status as the only known habitat for some of the world’s rarest creatures. These include:

- Assam Roofed Turtle – A critically endangered species found only in select riverine habitats.

- Hispid Hare – A small, elusive mammal adapted to the park’s grasslands.

- Golden Langur – A strikingly beautiful primate, found in very few locations worldwide.

- Pygmy Hog – The world’s smallest and rarest wild pig, once believed to be extinct until rediscovered in the park.

Mammals of Manas

Manas National Park is home to over 55 species of mammals, with 21 species classified under India’s Schedule I (highly protected) category. Some of the most notable mammals include:

- Bengal Tiger

- Indian Elephant

- Indian Rhinoceros

- Wild Buffalo

- Gaur (Indian Bison)

- Clouded Leopard

- Barking Deer

- Hog Deer

- Sloth Bear

- Leopard

- Asian Golden Cat

- Smooth-coated Otter

Birdlife: A Haven for Avian Species

With approximately 380 species of birds recorded in the park, Manas is a dream destination for birdwatchers. It is home to the highest population of the endangered Bengal Florican, along with a diverse range of resident and migratory birds, including:

- Great Hornbill

- Pied Hornbill

- Jungle Fowl

- Egrets

- Brahminy Ducks

- Scarlet Minivet

- Fishing Eagles

- Ospreys

- Serpent Eagles

- Falcons

Flora: The Lush Greenery of Manas

The park’s lush vegetation consists of semi-evergreen forests, grasslands, and riverine ecosystems. Some of the dominant tree species found here include:

- Syzygium cumini (Jamun)

- Anthocephalus chinensis (Kadamba)

- Dillenia indica (Elephant Apple)

- Terminalia chebula (Haritaki)

- Bombax ceiba (Silk Cotton Tree)

- Lagerstroemia speciosa (Pride of India)

- Gmelina arborea (Gamari)

The grasslands, which support a variety of herbivores, are primarily dominated by Imperata cylindrica, Saccharum naranga, and Phragmites karka.

The Significance of Manas National Park

Manas is not just a sanctuary for wildlife; it plays a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance. The diverse flora and fauna contribute to a stable ecosystem, making it an integral part of the Eastern Himalayan biodiversity hotspot. The park’s conservation efforts have led to the revival of many endangered species, making it a model for wildlife preservation in India.

Conservation Challenges and Efforts

Despite its rich biodiversity, Manas has faced several threats over the years, including:

- Poaching and Illegal Wildlife Trade – The park was severely affected by poaching during periods of political unrest. However, conservation programs have significantly reduced this threat.

- Deforestation and Encroachment – Expansion of human settlements has led to habitat loss, but afforestation initiatives are being implemented to restore lost greenery.

- Climate Change – Changes in weather patterns have affected the migration and breeding patterns of certain species.

Several organizations, along with local communities, have been actively involved in protecting and restoring the park’s natural wealth. Government initiatives and global conservation projects have played a key role in ensuring that Manas continues to thrive.

Conclusion

Manas National Park stands as a shining example of nature’s resilience and beauty. It is not just a protected area but a vital hub of biodiversity, housing some of the most endangered species on the planet. Conservation efforts have gradually restored its ecological balance, making it one of the most valuable wildlife reserves in India. As awareness about its significance grows, it is hoped that Manas will continue to be a safe haven for wildlife for generations to come.

FAQ’s:

What makes Manas National Park special compared to other wildlife reserves in India?

Manas National Park is unique because it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a Tiger Reserve, an Elephant Reserve, and a Biosphere Reserve. It is the only place in the world where rare species like the Assam Roofed Turtle, Hispid Hare, Golden Langur, and Pygmy Hog are found.

What type of wildlife can be seen in Manas National Park?

The park is home to a diverse range of animals, including tigers, elephants, Indian rhinoceroses, wild buffaloes, leopards, capped langurs, and barking deer. It also has over 380 species of birds, including the endangered Bengal Florican.

Why was Manas National Park declared a World Heritage Site in danger?

In 1992, UNESCO listed Manas as a World Heritage Site in danger due to poaching, habitat destruction, and conflicts in the region. Conservation efforts have improved the situation, and in 2011, it was removed from the danger list.

What are the main ecosystems found in Manas National Park?

Manas has two major ecosystems: the grassland biome, which supports species like the pygmy hog, Bengal florican, and wild Asian buffalo, and the forest biome, home to slow lorises, capped langurs, sambar deer, and Malayan giant squirrels.

How large is Manas National Park, and in which districts is it located?

The park covers an area of 950 sq. km and spans five districts in Assam: Kokrajhar, Chirang, Baksa, Udalguri, and Darrang. Its headquarters are at Barpeta Road.

What kind of trees and plants are found in Manas National Park?

Manas has a rich variety of trees, including sal, silk cotton, fig, Indian gooseberry, and several species of orchids. Its grasslands are dominated by tall elephant grass and riverine vegetation, making it a perfect habitat for herbivores.

When is the best time to visit Manas National Park?

The best time to visit is from November to February when the weather is pleasant, and animals are more visible. Heavy rainfall from May to September makes the park difficult to access.

How is Manas National Park helping in wildlife conservation?

Several conservation programs have helped revive animal populations in Manas, such as Project Tiger, the reintroduction of rhinos, and anti-poaching efforts. Community involvement and strict regulations have improved its wildlife protection measures.

Which birds are commonly seen in Manas National Park?

Birdwatchers can spot rare and beautiful birds like the giant hornbill, jungle fowl, scarlet minivet, fishing eagle, falcon, and pied hornbill. The park also has the largest population of the endangered Bengal florican.

How has Manas National Park recovered from past threats?

Due to conservation efforts, poaching has decreased, and animal populations are slowly increasing. UNESCO removed it from the endangered list in 2011, showing that the park’s ecosystem is improving with better protection and restoration programs.