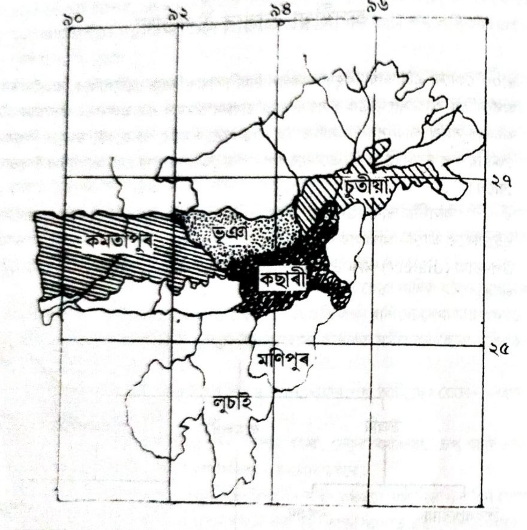

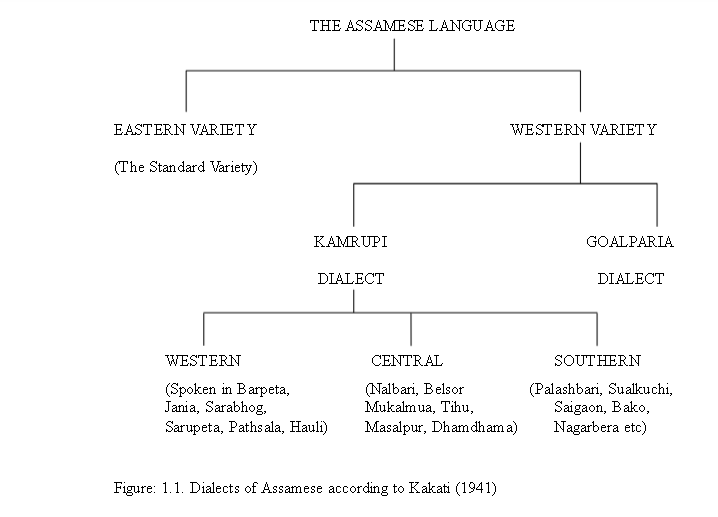

Assamese, an Indo-Aryan language spoken by over 15 million people primarily in the Indian state of Assam, exhibits rich dialectical diversity. The dialects of Assamese can broadly be categorized into Eastern, Central, and Western varieties, with further sub-dialects within each category. These dialectical variants reflect the linguistic and cultural diversity of the region, shaped by historical, geographical, and social factors.

Dialectical Variants of Assamese

- Eastern Assamese Dialects:

- Predominantly spoken in districts like Dibrugarh, Tinsukia, and Sivasagar, the Eastern dialects feature distinctive phonetic and lexical characteristics. This variety is often regarded as more “refined” or “classical” due to its proximity to the older literary forms of the language.

- Central Assamese Dialects:

- Spoken in districts such as Nagaon, Sonitpur, and Morigaon, the Central Assamese dialects serve as the basis for Standard Assamese. These dialects are generally perceived as more neutral, making them more comprehensible across different regions.

- Western Assamese Dialects:

- Found in areas like Kamrup, Nalbari, and Goalpara, the Western dialects incorporate influences from neighbouring Bengali and Bodo languages. These dialects often exhibit unique intonations and vocabulary that distinguish them from their Eastern and Central counterparts.

Usage of Standard Assamese on Social Media Platforms

With the advent of social media, the use of Assamese has seen a significant transformation. Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have become arenas for linguistic expression and innovation. The standard written form of Assamese, which is based on the Central dialect, is predominantly used in digital communication, owing to several factors:

- Comprehensibility:

- Standard Assamese is understood by a majority of the Assamese-speaking population, making it the preferred choice for communication on social media. It serves as a lingua franca that bridges the dialectical divides.

- Education and Media:

- The medium of instruction in schools and the language of print and electronic media in Assam is largely in Standard Assamese. This widespread use in formal settings reinforces its acceptance and familiarity among social media users.

- Uniformity and Standardization:

- On social media, users often prefer a standardized form of language to ensure clarity and avoid misunderstandings. Standard Assamese, with its codified grammar and vocabulary, provides this uniformity.

Despite the dominance of Standard Assamese in writing, social media also reflects the vibrancy of spoken dialects. Users frequently employ regional slang, idiomatic expressions, and phonetic spellings in their posts and comments, adding a layer of local flavour and authenticity to their communication.

Differences Between Written and Spoken Assamese

The gap between written and spoken Assamese is marked by several linguistic features:

- Phonological Differences:

Spoken Assamese often features contractions, elisions, and assimilations that are not present in the written form

- Lexical Variations:

The vocabulary used in spoken Assamese can differ significantly from the written form. Colloquial terms and regional words frequently appear in conversation but might be replaced by more standardized synonyms in writing.

- Syntax and Grammar:

Spoken Assamese tends to be more flexible with syntax and grammar. Informal speech might include sentence fragments, interjections, and non-standard grammatical constructions that are typically avoided in formal writing.

- Code-Switching and Code-Mixing:

Assamese speakers often switch between Assamese and English or other regional languages in conversation. This phenomenon is less common in written form, where a purer form of Standard Assamese is usually maintained.

Usage of free variation of /x/, /h/, and /kh/ in Assamese

In Assamese, there is an interesting phenomenon of free variation among the sounds /x/, /h/, and /kh/. This means that these sounds can be used interchangeably in certain words without altering the meaning, reflecting a level of phonetic fluidity within the language. Below are some examples and explanations of this free variation in Assamese dialects.

1. /x/ and /h/

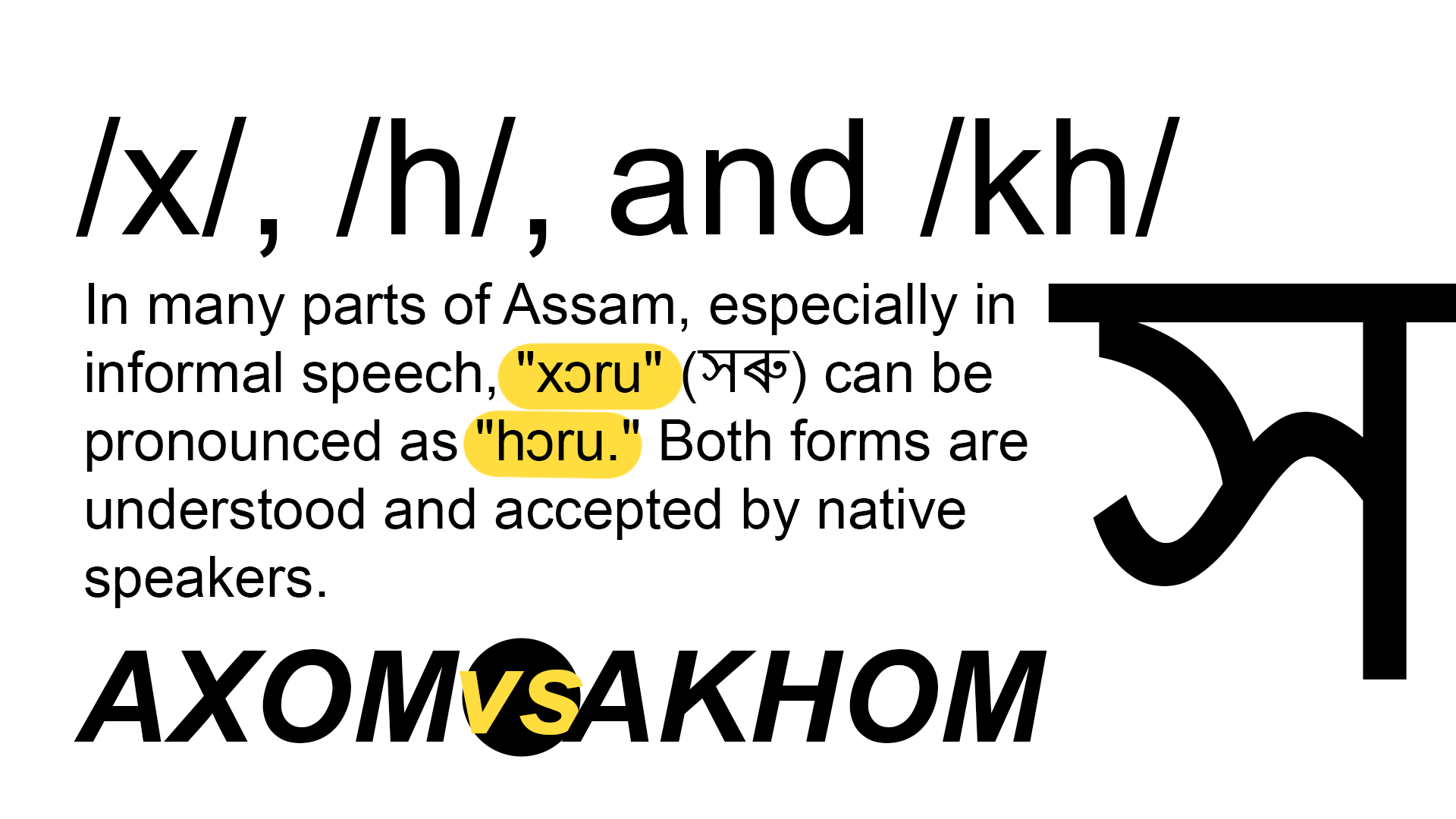

- Example 1: “xɔru” vs. “hɔru”

- Meaning: small

- Usage: In many parts of Assam, especially in informal speech, “xɔru” (সৰু) can be pronounced as “hɔru.” Both forms are understood and accepted by native speakers.

- Contextual Note: The /x/ sound is a voiceless velar fricative, while /h/ is a voiceless glottal fricative. This variation often occurs due to regional influences or personal speaking habits.

- Example 2: “xɔkɔlu” vs. “hɔkɔlu”

- Meaning: all

- Usage: “xɔkɔlu” (সকলো) is often heard as “hɔkɔlu.” The interchange between /x/ and /h/ does not change the meaning, making both pronunciations equally valid in conversation.

- Contextual Note: This variation is more common in Western Assamese dialects where /h/ is more prevalent.

2. /x/ , /h/ and /kh/

- Example 1: “xika” “hika” and “khika”

- Meaning: Teach

- Usage: The word “xika” (শিকা) can also be pronounced as “hika” , “khika”. These variations are understood and used interchangeably by speakers.

- Contextual Note: The /kh/ sound is an aspirated voiceless velar plosive. This free variation highlights the fluidity between fricative and plosive sounds in Assamese.

- Example 2: “xɔdai” vs. “khɔdai”

- Meaning: Always

- Usage: “xɔdai” (সদায়) is sometimes pronounced as “ khɔdai.” This interchangeability does not affect the comprehension of the term.

- Contextual Note: The choice between /x/ and /kh/ can be influenced by factors such as speaker’s region and context of speech.

The free variation among /x/, /h/, and /kh/ in Assamese demonstrates the language’s phonetic flexibility and regional diversity. These variations are accepted in everyday speech and reflect the dynamic nature of Assamese phonology. Understanding these nuances provides insight into the rich linguistic tapestry of Assam and aids in appreciating the subtleties of its dialects.

Vowel Deletion

Deletion of vowels is very prevalent in BD. It is obvious that deletion usually occurs in Borpetia Dialect at the time of affixation. Given below are some cases of deletion in Borpetia Dialect.

Deletion in the suffix with a closed or consonant final monosyllabic root

- xuk-ɔni → xuk.ni (dry- ADJ state of drying)

- suk-ɔna → suk.na (scoop-NOM an instrument to scoop)

- kɔr-isil → kɔr.sil (do-PST)

Deletion in the suffix with an open monosyllabic root

- pa:-isili → pais.li (get-PST)

- kʰa:-isilu → kʰais.lu (eat-PST.1 ga:-isila → gais.la sing-PST)

Deletion in the 2nd closed syllable of the root

a. pit.ik-isu → pit.ki.su (fondle-PST)

b. dʰer.ek-ibɔ → dʰer.ki.bɔ (thunder-FUT)

In certain cases, Nalbaria prefers a sequence of CV.CV as opposed to standard

Assamese CVC. This is done by inserting an additional vowel at the end by making the coda consonant an onset of the inserted vowel. The result is an increased number of syllables within a word. Usually, this epenthetic vowel is a low vowel /a/. For example,

Standard Assamese Nalbaria

/tam/ /tama/ ‘copper’

/xon/ /xɔna/ ‘gold’

/kah/ /kaha/ ‘brass’

/pal/ /pala / ‘turn’

Refer to the book on Assamese Dialects below for more clarity:

assam-dialect-bookConclusion

The dialectical diversity of Assamese is a testament to the rich cultural tapestry of Assam. While Standard Assamese has become the norm on social media platforms due to its widespread acceptance and comprehensibility, the influence of regional dialects remains strong in spoken communication. This dynamic interplay between the standard and dialectical forms enriches the language, reflecting its adaptability and resilience in the digital age. Social media, thus, not only preserves the standard form but also celebrates the vibrant dialectical variations that make Assamese a truly unique language.

Sources and References:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hemkosh

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assamese_language

- Patgiri, Bipasha. “Syllabification and Stress Pattern.” In Chapter 2.

- Morey, Stephen, and Post, Mark, eds. North East Indian Linguistics Volume 2. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Kakati, Banikanta. “Preface to the First Edition.” In Assamese: Its Formation and Development, 1941.